PIV Details

You can use these simple methods to view, export, and understand the information stored on a PIV credential.

View Your PIV Credential Certificates

Almost all of the methods for using your PIV credential for networks, applications, digital signatures, and encryption involve the certificates and key pairs stored on your PIV credential. There are also scenarios where additional information (such as biometrics) is also accessed and used.

To view your certificate information:

- Insert your PIV credential into your card reader.

- Choose an option from the table below and follow the steps.

| Operating System | Module | Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Microsoft | Internet Explorer | Open Internet Explorer Browser > Tools Wheel or (Alt+X) > Internet Options > Content Tab > Certificates Button > Personal Tab |

| Microsoft | Microsoft Management Console (MMC) and Certificate Snap-in | Open Microsoft Management Console > File > Add/Remove Snap-In > Certificates Snap-in > Add > My user account > Finish > Expand Certificates - Current User > Personal > Certificates |

| Any | Chrome Browser | Open Chrome Browser > Settings > Show Advanced Settings > Manage Certificates (Manage HTTPS/SSL Certificates and Settings) > Personal tab |

| Any | Firefox Browser | Open Firefox Browser > Settings wheel > Privacy & Security > Security > Certificates > View Certificates button > Certificates Manager > Your Certificates Tab |

| macOS X | Keychain | Open Applications > Utilities > Keychain Access > Select Login > Categories > My Certificates |

View

You may see many certificates. To open and view the certificate details, double-click on any certificate.

Export PIV Certificates

We won’t always use graphical user interfaces to view the PIV credential certificates. Throughout the PIV and the Federal PKI (FPKI) Guides, we’re continuing to add useful procedures for network engineers and examples of code, tools, and common command line options for viewing and troubleshooting configurations. (Note: These examples may use files representing public certificates.)

Export

Look for an Export button and save the file as DER or PEM-encoded, with a file extension of cer (.cer).

Keys are safe!

Don't worry; the public certificates are public. The private keys are always stored safely on your PIV credential and can never be exported.

PIV Certificates

Viewing the certificate information on your PIV credential may be interesting if you are a general user. You must understand certificate information as a program manager or engineer developing applications and designing solutions for using PIV credentials.

Within the U.S. federal government, the certificate and PIV credential information is governed by standards, policies, and implementation-specific choices (options) across all agency credential providers.

Typically, there are four certificates and four key pairs on a PIV credential. However, one pair (i.e., one certificate and one key pair) is ALWAYS on every PIV credential and three pairs (i.e., three certificates and three key pairs) are SOMETIMES on a PIV credential. You can review the PIV Overview to view the four pairs and purposes.

The table below outlines the general information for the PIV credential certificates, certificate extensions, and design considerations.

6 Years

PIV credentials and certificates have changed over time due to updates in standards. Since users may have credentials for up to 6 years and there are both optional and mandatory elements, the information presented is what is valid for ALL PIV credentials and certificates currently in use. (Although credentials are valid for 6 years, the certificates contained on a credential are valid for only 3 years, with the exception of the content signer.)

| Certificate | Required | Key Usage | Extended Key Usage | Subject Alternative Name | Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIV Authentication | Always | Digital Signature | Client Authentication | otherName = FASC-N; uniformResourceIdentifier = UUID; Principal Name = prefix@suffix |

Principal Name values are not required by policy to be present in all Subject Alternative Name extensions. The Card UUID may also commonly be referred to as the Global Unique Identifier (GUID). |

| Card Authentication | Always | Digital Signature | id-PIV-cardAuth | Name = FASC-N; uniformResourceIdentifier = UUID |

Card Authentication must be included in new and replacement PIV credentials issued after August 2014; it is not expected that all PIV credentials will have Card Authentication certificates until September 2019. The Card UUID may also commonly be referred to as the GUID. |

| Digital Signature | Sometimes | Digital Signature, Non-Repudiation | Specific EKUs are required for certificates issued after June 2019 | rfc822name = email address | Email address is not required by policy. Email address may be multivalued attributes and include email aliases. |

| Encryption | Sometimes | Key Encipherment | Specific EKUs are required for certificates issued after June 2019 | rfc822name = email address | Email address is not required by policy. Encryption certificates that represent available, retired encryption key pairs may exist, depending on the PIV issuer. |

| PIV Content Signer | Always | Digital Signature | id-PIV-content-signing | N/A | The PIV content signer ensures the integrity of the digital information stored on the card. Physical Access Control Systems (PACS) are the primary relying party for these certificates. This certificate is unavailable in most logical trust stores, but users can leverage the Card Conformance Tool (CCT if they would like to extract and view the PIV content signing certificate. |

Additional useful information:

- All key pairs for users are 2048-bit (RSA) keys.

- All certificates issued and certified as PIV are SHA-256 signed.

- If you are working with Common Access Cards, you may still encounter SHA-1-signed certificates and might not see a Card Authentication certificate.

- There has been testing in some infrastructures to migrate to Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), but there are no ECC certificates for users in production as of the date of this guide.

- There has been testing in some infrastructures to migrate to 3072-bit (RSA) certificates, but there are no 3072-bit certificates for users in production as of the date of this guide.

In-depth details on the certificate profiles are contained in the current and historical Federal Public Key Infrastructure (FPKI) policy documents. The most recent policy and certificate profile documents may be found on IDManagement.gov’s FPKI Policy and Compliance Audit page.

PIV Identifiers

In applications including network domains, you will associate the PIV credential with your accounts. This process is not unique to PIV credentials and usage; it is a general concept that occurs in many applications, including your personal email accounts, your bank accounts, or your favorite social media app.

Associating a credential with an account is called account linking.

Identifiers are the values in credentials that are used for account linking. We focus on the PIV Authentication certificate and identifiers in this section to help you understand the options and design and implement solutions for using PIV to authenticate to networks and applications. For more information on account linking, see Account Linking .

The table below outlines identifiers available in the PIV Authentication certificate and design considerations for implementations.

| Identifiers | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Subject | Unique for every person within the same agency; value does not change when a user receives a new, replaced, or updated PIV credential within the same agency. |

| Issuer and Subject | Unique for every person; value does not change when a user receives a new, replaced, or updated PIV credential within the same agency. |

| Issuer and Serial Number | Unique for every person and certificate; value changes when a user receives a new, replaced, or updated PIV credential. |

| Subject Key Identifier | Unique for every person and certificate; value changes when a user receives a new, replaced, or updated PIV credential. |

| SHA-1 Hash of Public Key | Value changes when a user receives a new, replaced, or updated PIV credential; commonly referred to as the thumbprint of the certificate. |

| Federal Agency Smart Card Number (FASC-N) | It is not recommended to use the FASC-N as an identifier; unique for every credential only within the U.S. federal Executive Branch agencies; no uniqueness for PIV credentials issued by Legislative or Judicial Branch agencies, state, local, tribal, territories, partners, or any credentials certified as PIV-Interoperable or PIV-I; value changes when a user receives a new, replaced, or updated PIV credential; legacy definition and usage supported building access control systems as outlined in Technical Implementation Guidance: Smart Card Enabled Physical Access Control Systems) (PDF, 2005). |

| Card Universal Unique Identifier (UUID) | Unique for every person and credential; value changes when a user receives a new, replaced, or updated PIV credential; Card UUID value is only required to be present for new or replacement PIV credentials issued after August 2014; may also commonly be referred to as the Global Unique Identifier (GUID). |

| User Principal Name in Subject Alternate Name | Not required to be included in all PIV Authentication certificates; not recommended for use as an identifier to achieve full interoperability for networks or applications; commonly used for enterprise smart card logon / network authentication in legacy implementations. |

For all items referencing an agency in the table, you should consider the reference as the small organizational unit. For example, a user who switches between one component in a large agency to another component may receive a new Subject Name when the user requires a replacement PIV credential.

Organization Specific Identifiers

Multiple departments and agencies leverage a persistent, internal unique identifier. For example, the Department of Defense uses a unique 10-digit identifier called the Electronic Data Interchange Personal Identifier or EDIPI. The Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Health and Human Services leverage a similar persistent lifetime identifier for their identities. Note that these identifiers are unique within the systems that generate them. There is a risk of collision when leveraging these identifiers in external systems.

Two common questions about PIV are: “What are all these certificates, and how do I configure my applications to use them?” Answering these questions involves explaining trust, certificate chains, and revocation.

If you are looking for the root certificates, you can quickly jump to the end of the page for instructions.

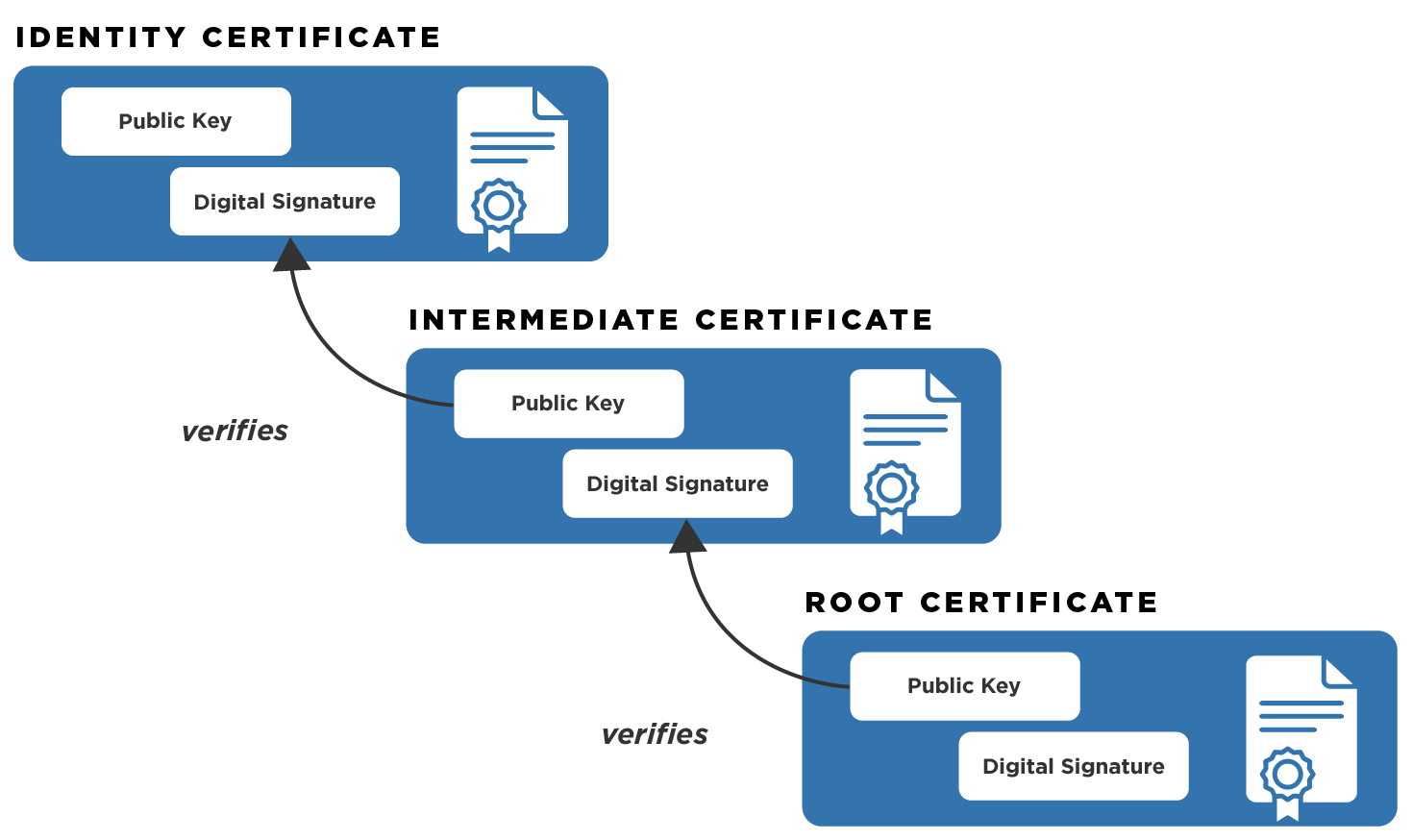

Trust

Identity certificates are issued and digitally signed by a certification authority (CA). The CA that signed your PIV certificates is called an intermediate CA because it was issued a certificate by another CA. This process of issuing and signing continues until there is one CA that is called the root CA.

The full process of proving identity when issuing the certificates, auditing the certification authorities, and the cryptographic protections of the digital signatures establish the basis of trust for PIV credentials and certificates.

For the federal government Executive Branch agencies, there is one root CA named Federal Common Policy Certificate Authority G2 (FCPCAG2 or COMMON) and there are dozens of intermediate CAs. The federal government has also established trust with other CAs that serve business communities, state and local government communities, and international government communities.

The participating CAs are subject to policies, processes, and auditing collectively referred to as the Federal Public Key Infrastructure (FPKI)

The FPKI Graph is an interactive chart of the Federal Public Key Infrastructure CAs, including cross-certified business communities.

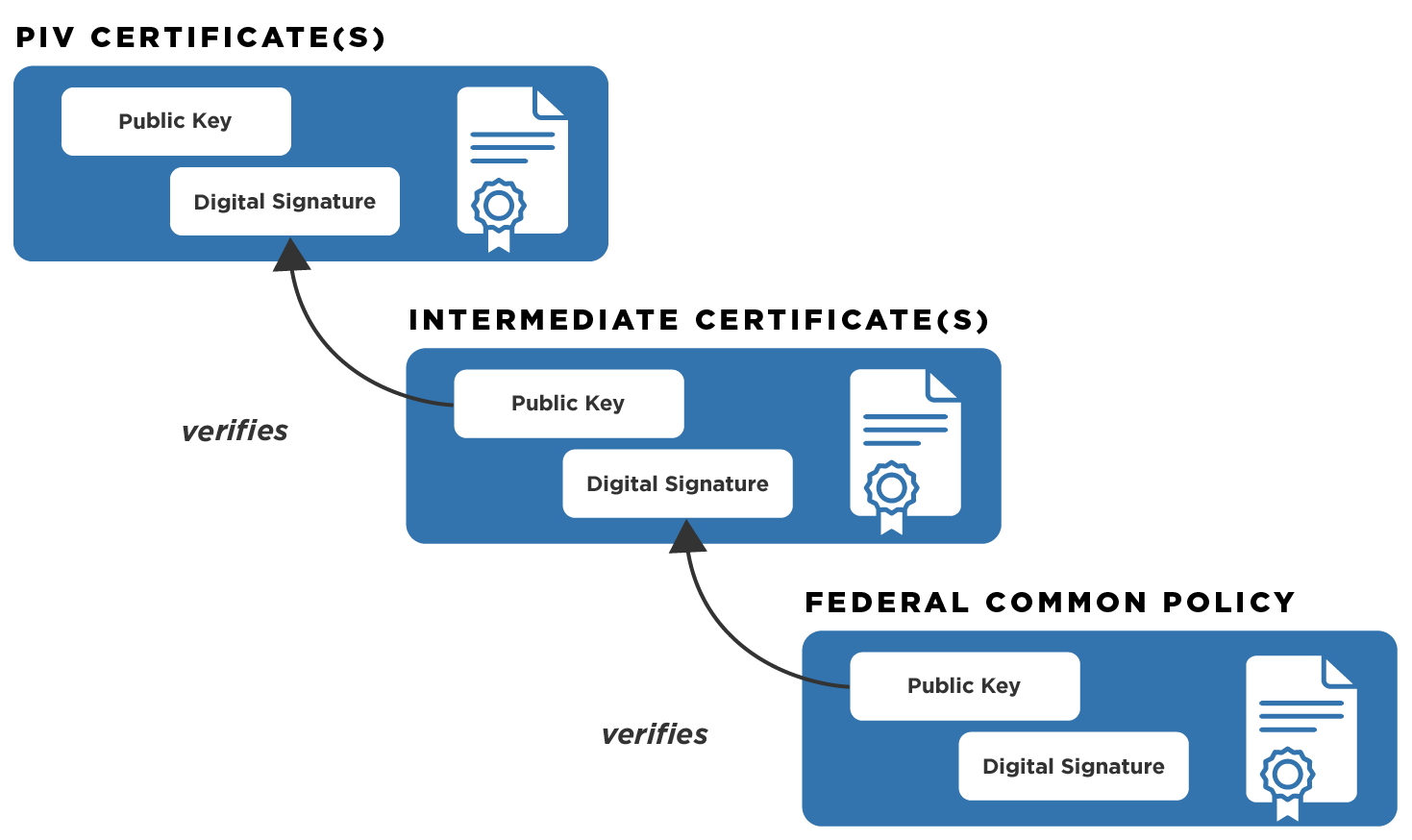

Certificate Chains

To digitally trust YOU and your PIV credential certificates, the workstations, servers, applications, and network domains will be configured. Understanding and managing certificate chains are one of the methods to configure trust.

The certificate chain includes the intermediate CA certificates and the Federal Common Policy Certification Authority G2 (COMMON) root certificate.

Federal PKI Person Root - COMMON

The Federal Common Policy Certification Authority G2 (COMMON) root certificate is included in Adobe trust stores by default. It is not included by default in Microsoft, Apple, Mozilla, Java, all mobile device operating systems, or Linux based operating systems.

If you are an engineer working on implementing PIV authentication, you may need to download and install the root certificate (COMMON) for your workstations, servers, applications and network domains.

Many applications may require intermediate certificates to successfully trust ALL PIV credentials and may not support the automatic retrieval of certificate chains. You should consider the possible unintended consequences of installing intermediate certificates which only represent intermediate certificate chains for your agency users. You may want to be able to trust all PIV credentials from agencies and credentials from our trusted partners. It is increasingly more common for users from other agencies or partners to authenticate to your networks or applications; this usage is the foundation of PIV to promote trust, interoperability, authentication, and efficiency across the U.S. federal government.

General recommendations for trust and certificate chain management include:

- COMMON should be used as the trusted root CA.

- Management of root and intermediate CA certificates and distribution to network domains, workstations, servers and applications should be managed with group policy objects, secure automated distributions mechanisms, and enterprise policies and procedures to ensure updates are managed effectively.

- NIST published an Information Technology Laboratory (ITL) bulletin in July 2012 which includes general practices to consider.

Installation of the trusted root certificate and intermediate certificates is dependent upon operating systems and applications. Instructions for downloading certificates are at the end of this page.

Certificate Revocation

Revocation is the process and technology used to identify a certificate as no longer valid—to tell computers and applications “do not trust this certificate anymore.”

PIV credential certificates will be revoked when a user terminates employment or a contract with an agency, is issued a new credential, is issued an updated PIV credential, or has a lost, stolen, or damaged PIV credential. The revocation of PIV credential certificates occurs with the PIV credential issuer and CA.

There are two protocols available to verify if a PIV credential certificate has been revoked:

- Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP)

- Certificate Revocation Lists (CRLs)

Some implementations also validate whether the intermediate CA certificates have been revoked. While revocation of an intermediate CA certificate does not occur often, it is a safeguard in place and each intermediate CA and COMMON also publishes CRLs for the certificates signed next in the chain.

The table below outlines general information on each protocol, the certificate extension that contains the reference, and design considerations.

| Type | Certificate Extension | Protocol (Port) | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCSP | Authority Information Access | HTTP (80) | All PIV certificates have OCSP references and OCSP responder web services which are Internet accessible and provided by the issuing CA. Intermediate CAs are not required to have OCSP available for the intermediate certificates. |

| CRL | CRL Distribution Point (CDP) | HTTP (80) | All PIV certificates have CRL references and CRLs files published to Internet accessible web services by the issuing CA. All intermediate CA certificates also have CRL references, files, and Internet accessible web services. CRL files have an expiration time that varies between 6 to 18 hours. CRL file sizes distributed by issuing CAs as of the date of this guide range from a few kilobytes to more than 30 megabytes (MB). |

For a portion of your implementations such as network authentication, the revocation checks will occur as part of the operating system or server native functionality. Other implementations may want to consider services such as implementing Server Certificate Validation Protocol (SCVP). These are advanced topics to consider and will be covered in other areas of the guides soon.

Download Root and Intermediate Certificates

The federal government recently deployed the Federal Common Policy CA G2 (FCPCAG2), a new Federal Public Key Infrastructure (FPKI) root CA. As the existing Federal Common Policy CA reaches the end of its planned service life, FCPCAG2 will roll out incrementally and serve as the new trust anchor for the Federal PKI. Below, you’ll find important dates and steps for a successful operational transition to the FCPCAG2 trust anchor.

For instructions on how to download the new root and intermediate certificates, go to the FPKI guide on the Federal Common Policy G2 Update

Download Any Additional Intermediate Certification Authority Certificates

You can contact your agency’s information security teams for help with additional intermediate certificates, or you can find the intermediate certificates by using information in your PIV certificates directly.

- View your PIV Authentication certificate. To review how to view your PIV Authentication certificate, go to the PIV Details

- In the Authority Information Access (AIA) extension, there is a URL (http://) that references a file with a .p7b or .p7c extension.

- Download the file, open it, and view the intermediate CA certificates.

- Repeat the process using the AIA extension of the intermediate CA certificates until the final reference finds an intermediate CA certificate that is issued and signed by COMMON.

Many products and implementations may automatically retrieve the intermediate certificates during a process called certificate path building or certificate path discovery. You will encounter varying implementations of the certificate path discovery process based on differences in client operating systems, browsers, mobile devices, programming languages, and even applications directly. It can be challenging to understand all the options that impact your users and applications; we are seeking input and contributions to expand this information for you.

We want to add more information to help you, so check back often or review the Issues posted and consider contributing!